Simulation and Recovery with PMwG

This blog post presents a brief guide on how to create synthetic data, and perform parameter recovery, using the PMwG sampler. Parameter recovery is highly important in cognitive modelling procedures as it provides an indication of parameter identifiability (and in a way, model “power”). Parameter recovery involves creating synthetic data using a likelihood function, checking the synthetic data, performing a sampling regime and then checking the posterior estimates (as well as posterior predictive data). It is an essential step in the modelling process.

Parameter recovery through simulation allows us to be confident in our models for three reasons. First, it gives us confidence that our model actually works, i.e. it runs, it relates to data, it does what it’s supposed to do. Secondly, parameter recovery allows us to see whether the parameter values we input are recovered at the end, and this can give us confidence in the reliability of our model. Finally, parameter recovery allows us to test a variety of parameter combinations and models, which can test theory and help us build hypotheses.

Synthetic data

Synthetic data is data generated from your model. When simulating this synthetic data, we make a data set that looks just like real data (i.e. same structure), with the aim of later replacing it with real data. We also want this synthetic data to reflect real data - i.e. somewhere in the ballpark of means and variance. When generating synthetic data, we input parameter values that we decide (or could be informed by prior research) and then use a random generator function (like rnorm, rlba or rddm), that takes in these values to create data.

By creating synthetic data, we are able to control the input parameters, and so we are able to better understand how parameters affect synthetic data - i.e. whether changing given parameters changes output. Secondly, we are able to see if the original values are recovered following sampling, therefore showing how well the model identifies the actual effects. Finally, we can see how well the posterior predictive data fits the synthetic data. Often different parameters may lead to similar patterns in the data (i.e. higher thresholds and higher t0 can show similar increases in rt for accumulator models), so by comparing to the posterior predictive, this can give us an indication of whether our model can tease apart parameter differences.

Within PMwG, there is an assumed hierarchical structure, with group level (theta) and individual participant level (alpha) values. On each iteration of the sampling process, n particles density are compared (given the data). These particles are drawn from a multivariate normal distribution centered around each participants current particle (with added noise). To create this multivariate normal distribution, the sampler also uses a covariance matrix, which gives insight into the level of covariance between individual parameters. This makes simulating synthetic data for the PMwG sampler slightly more complex, as simulated parameters should also have a covariance structure constraining them. This is shown below.

In this blog post I will;

- construct the data structure

- construct a likelihood function with sampling and density calculation arguments.

- create some parameters for the model

- fill in the values for these parameters

- constrain by the covariance matrix

- create data

- perform parameter recovery.

Simulation

Starting out

First I load in the packages used for this exercise;

library(rtdists)

library(mvtnorm) ## For the multivariate normal.

library(MASS) ## For matrix inverse.

library(MCMCpack)

library(lme4)

library(dplyr)

library(ggplot2)

library(tidyr)Data structure

Next, we set up the structure of the data frame to be filled with data. For this exercise, i use 3 conditions, each with 100 trials for 20 participants. You can create whatever data structure you wish, however, it should map to your likelihood function, should be the same as your real data (or at least the parts of your real data used in the likelihood function) and can be any length (but more is better). I do this setup step first as this often assists with writing the likelihood function (i.e. for correct column names and data structure).

n.trials = 100 #number trials per subject per conditions

n.subj = 20 #number of subjects

n.cond = 3 #number of conditions

names=c("subject","rt","resp","condition") #names of columns

data = data.frame(matrix(NA, ncol = length(names), nrow = (n.trials*n.subj*n.cond))) #empty data frame

names(data)=names

data$condition = rep(1:n.cond,times = n.trials) #filling in condition

data$subject = rep(1:n.subj, each = n.trials*n.cond) #filling in subjectsConstruct the model

Now that the data structure has been created, I need to establish my model. The model I use here is similar to that used in Chapter 3 of the PMwG Documention. This model is a LBA model which includes 3 different thresholds (differing across conditions).

log_likelihood=function(x,data,sample=TRUE) {

x=exp(x)

bs=x["A"]+x[c("b1","b2","b3")][data$condition]

if (sample) { #for sampling

out=rLBA(n=nrow(data),A=x["A"],b=bs,t0=x["t0"],mean_v=x[c("v1","v2")],sd_v=c(1,1),distribution="norm",silent=TRUE)

} else { #for calculating density

out=dLBA(rt=data$rt,response=data$correct,A=x["A"],b=bs,t0=x["t0"],mean_v=x[c("v1","v2")],sd_v=c(1,1),distribution="norm",silent=TRUE)

bad=(out<1e-10)|(!is.finite(out))

out[bad]=1e-10

out=sum(log(out))

}

out

}In this example, I use responses “1” and “2”, but you can use whatever responses you would prefer (i.e. correct or error etc). Further, you could also use a different model type (i.e. diffusion).

Create model parameters

Next, I create my parameter vector;

parameter.names=c("b1","b2","b3", "A","v1","v2","t0")

n.parameters=length(parameter.names)Now i set up a vector of parameter values and a matrix of covariance matrix values. I label these ptm and ptm2;

ptm <- array(dim = n.parameters, dimnames = list(parameter.names)) #an empty array where i will put parameter values

pts2 <- array(dim=c(n.parameters,n.parameters), dimnames = list(parameter.names,parameter.names)) #an empty array where i will put the covariance matrixFill in model parameters

I then give start points for my input parameters. Here, I use increments of 0.2 for the threshold parameters. It is important to consider a number of different values to see if, and how, they affect the simulated data (but you can do this later). For example, I may also want to vary t0 or drift rates (i.e. different models) to see if these parameters are also recoverable.

NOTE: these values are on the log scale (as the likelihood function takes the exponent of these). This is important to note as PMwG draws values along the real number line.

ptm[1:n.parameters]=c(0.1,0.3,0.5,0.4,1.2,0.3,-2)

exp(ptm)

## b1 b2 b3 A v1 v2 t0

## 1.1051709 1.3498588 1.6487213 1.4918247 3.3201169 1.3498588 0.1353353Create covariance matrix

Next, I make the variance of the parameters. I do this in a simple way by taking the absolute value for each parameter and divide by 10 - but you can vary them however you like, for example, there may be covariances that are important to the model. In this example with the LBA, it might be better to put larger correlations between b and t0.

In this code, SigmaC is a matrix with diagonal of 0.2 (i.e. a correlation of .2 between all parameters), and off diagonal as the variance we just created. I then do sdcor2cov to create a covariance matrix. I do this because, rather than correlation, PMwG expects covariance. You can do the opposite transform to recover these correlations after recovery.

This step is the tricky part of simulating in PMwG, as we need this correlation structure (which becomes a covariance structure) to constrain parameters.

vars = abs(ptm)/10 #off diagonal correlations are done as absolute/10

sigmaC = matrix(.2,nrow=length(ptm),ncol=length(ptm)) ###std dev correlation on diagonal - you might think this should be corr = 1, but it's actually the standard deviation

diag(sigmaC)=sqrt(vars)

sigmaC <- sdcor2cov(sigmaC)Create random effects

Finally, I create the subjects random effects. This is a n_parameters * n_subject matrix, so that each subject has a value for each parameter. This is created using rmvnorm, where I do n_subjects of random samples using the mean parameters (ptm) and covariance matrix (sigmaC). These are the values we wish to recover using the model (so it’s often good to save out ptm, sigmaC and subj_random_effects).

subj_random_effects <- t(mvtnorm::rmvnorm(n.subj,mean=ptm,sigma=sigmaC))

## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6]

## b1 0.06754572 0.16595634 -0.14890327 0.007714805 0.22501307 0.04926983

## b2 0.45809512 0.01340640 0.08264425 0.460439178 0.30218297 0.23504860

## b3 0.58720469 0.37898141 1.13992801 0.573482556 0.32560658 0.63982060

## A 0.04662982 0.47198462 0.30647877 0.399114046 0.37684673 0.36270810

## v1 0.81182229 0.72201092 1.25883303 1.574770678 1.08952060 1.14255482

## v2 0.20903875 0.03129003 0.33744775 0.210704343 0.05004988 0.27938543

## t0 -1.75064334 -2.78634793 -1.26680060 -1.729459232 -2.60528073 -1.86775101

## [,7] [,8] [,9] [,10] [,11] [,12]

## b1 0.1242662 0.1685503 0.02285856 0.1965128 0.1384761 -0.1783804

## b2 0.2630983 0.1563505 0.32340648 0.1680148 0.4791735 0.2025268

## b3 0.6912657 0.7539752 0.21982543 0.5844972 0.5919369 0.4334701

## A 0.2050011 0.5426899 0.13960102 0.4180867 0.4450346 0.2092065

## v1 1.3145116 1.2392363 0.81793618 1.5938252 1.4879329 0.7255356

## v2 0.5693084 0.4971342 0.32438670 0.3977475 0.3670363 0.1248367

## t0 -3.1241916 -2.1788509 -2.25873295 -1.3214511 -1.8642588 -2.7759320

## [,13] [,14] [,15] [,16] [,17] [,18]

## b1 0.2058493 0.009413219 0.2026047 0.09626992 0.16157925 0.03773296

## b2 0.2836621 -0.071166522 0.1187272 0.26290527 0.17193572 -0.01895990

## b3 0.4004229 0.301991774 0.1302980 0.61103915 0.24588443 0.34190158

## A 0.6057064 0.143238731 0.3268137 0.31840193 0.50836559 0.49358757

## v1 1.6789963 0.999523427 2.0098674 1.39139828 1.31009377 0.66862124

## v2 0.4274261 0.444679107 0.3446718 0.36219300 0.07455863 0.47500308

## t0 -2.2730857 -2.881332602 -2.4249129 -1.93661795 -1.87873689 -2.30251849

## [,19] [,20]

## b1 0.1225545 0.07948995

## b2 0.1557267 0.32662834

## b3 0.5413826 0.29090185

## A 0.4638920 0.54914061

## v1 1.1878292 1.49936441

## v2 0.3606136 0.30283934

## t0 -2.2716049 -1.85730079Create data

Using the likelihood function, I now run a for loop to create data and fill that empty matrix we made at the start! The likelihood returns both rt and resp, so the lower two lines fill in the appropriate columns in the data frame. The for loop runs for each subject, and so I input the subj_random_effect for each participant and fill the appropriate place in the data structure.

NOTE: It is important to check the data and general trends from the output. This can give an indication of how different parameters and covariance affect the data.

for (i in 1:n.subj){

tmp<- log_likelihood(subj_random_effects[,i],sample=TRUE,data=data[data$subject==i,])

data$rt[data$subject==i]=tmp$rt

data$resp[data$subject==i]=tmp$response

}

head(data)## subject rt resp condition

## 1 1 1.7090777 2 1

## 2 1 0.9500044 1 2

## 3 1 1.1687292 2 3

## 4 1 0.9118316 2 1

## 5 1 1.2868745 1 2

## 6 1 1.0794218 2 3We now have synthetic data which; - is generated using our model - uses theta values we input - uses a covariance structure we created

This means that these objects can be recovered.

Recovery

I now run a typical PMwG sampling exercise. Here the likelihood is unchanged from the PMwG documentation. I use broad priors and do not specify any start points. Following the adaptation stage, i take 1000 samples from the posterior.

NOTE: Running this on your own machine may be time consuming (and resource consuming). You may want to run it on a grid or dial down the number of cores used in sampling and wait it out.

library(pmwg)

# Specify the log likelihood function -------------------------------------------

lba_loglike <- function(x, data, sample = FALSE) {

x <- exp(x)

if (any(data$rt < x["t0"])) {

return(-1e10)

}

if (sample){

data$rt=NA

data$resp = NA

}

bs <- x["A"] + x[c("b1", "b2", "b3")][data$condition]

if (sample) {

out <- rtdists::rLBA(n = nrow(data),

A = x["A"],

b = bs,

t0 = x["t0"],

mean_v = x[c("v1", "v2")],

sd_v = c(1, 1),

distribution = "norm",

silent = TRUE)

data$rt <- out$rt

data$resp <- out$resp

} else {

out <- rtdists::dLBA(rt = data$rt,

response = data$resp,

A = x["A"],

b = bs,

t0 = x["t0"],

mean_v = list(x["v1"],x[ "v2"]),

sd_v = c(1, 1),

distribution = "norm",

silent = TRUE)

bad <- (out < 1e-10) | (!is.finite(out))

out[bad] <- 1e-10

out <- sum(log(out))

}

if (sample){return(data)}

if (!sample){return(out)}

}

# Specify the parameters and priors -------------------------------------------

# Vars used for controlling the run

pars <- c("b1","b2","b3", "A","v1","v2","t0")

priors <- list(

theta_mu_mean = rep(0, length(pars)),

theta_mu_var = diag(rep(9, length(pars))))

# Create the Particle Metropolis within Gibbs sampler object ------------------

sampler <- pmwgs(

data = data,

pars = pars,

prior = priors,

ll_func = lba_loglike

)

# start the sampler ---------------------------------------------------------

sampler <- init(sampler) # i don't use any start points here

# Sample! -------------------------------------------------------------------

burned <- run_stage(sampler, stage = "burn",iter = 500, particles = 100, n_cores = 16) #epsion will set automatically to 0.5

adapted <- run_stage(burned, stage = "adapt", iter = 5000, particles = 100, n_cores = 16)

sampled <- run_stage(adapted, stage = "sample", iter = 1000, particles = 100, n_cores = 16)

We now have samples from our model which is fitted to the simulated data! You should check that the sampling process worked well before continuing on. To check this process, see the guide in the PMwG documentation.

Checking and Simulating posterior predictive data

We now have 1000 posterior samples. From here, there are several steps we want to take to check how well parameters recover. First, we’ll check the mean posterior theta estimates. Then we’ll check the alpha (random effects) estimates, before checking the covariance matrix. For extra checking, I’ll then simulate data from the posterior to see how well the data recovers.

Checking the theta, alpha and covariance matrix

The first check I do is to see whether our ptm values and subj_random_effect recovered following simulation and sampling. I first do this at the group (theta) level;

theta <- apply(sampled$samples$theta_mu[,sampled$samples$stage=="sample"],1,mean) #gets the

exp(theta) #done for convenience of interpretation

## b1 b2 b3 A v1 v2 t0

## 0.8832800 1.0173988 1.4128471 1.5383791 3.3117580 1.1322673 0.1540344

exp(ptm)

## b1 b2 b3 A v1 v2 t0

## 1.1051709 1.3498588 1.6487213 1.4918247 3.3201169 1.3498588 0.1353353And then at the subject (alpha) level;

alpha <- apply(sampled$samples$alpha[,,sampled$samples$stage=="sample"],1:2,mean)

exp(alpha)

## 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

## b1 0.7827243 0.9245987 0.7371639 0.8802455 0.9560409 0.8955390 0.82912937

## b2 1.0776528 0.8313766 0.8328184 1.5171650 1.1111514 1.1415803 0.98725643

## b3 1.4462429 1.1987399 2.8858160 1.7338225 1.1443454 1.6979257 1.58823062

## A 1.2372040 1.6414723 1.5708520 1.4744584 1.7530787 1.5733772 1.42484902

## v1 2.0723960 2.0740149 3.5780296 4.6794195 2.8813526 3.0778612 3.65466091

## v2 0.9351639 0.7248956 1.0610496 0.9406761 1.1274176 1.0988563 1.23011158

## t0 0.2202784 0.1229796 0.2960367 0.1865906 0.1174551 0.1609932 0.09479353

## 8 9 10 11 12 13 14

## b1 0.8361656 0.8167511 0.7924110 0.9002450 0.69403112 0.9664530 0.88863815

## b2 0.6926256 1.0854374 0.7986617 1.4237268 0.96883862 1.1169777 0.81015438

## b3 1.7298796 0.8970793 1.4943264 1.6228472 1.31072072 1.2897463 1.18800982

## A 1.8387425 1.1814593 1.6525283 1.5502767 1.57883116 1.6410829 1.41700250

## v1 3.2886217 2.0794062 4.8889854 4.3015547 2.07489764 4.8543457 2.73883101

## v2 1.1496684 1.1439376 1.1135874 1.1787368 1.11566670 1.1968833 1.63773055

## t0 0.1869287 0.1638233 0.3126664 0.1922919 0.09447705 0.1224144 0.09564317

## 15 16 17 18 19 20

## b1 1.0291379 0.9820875 1.0576247 0.9419080 0.8476923 1.0358966

## b2 0.7931455 1.2592877 1.0747271 0.9097072 1.0572080 1.2957602

## b3 0.8598098 1.7561695 1.3005711 1.2929230 1.6198270 1.3100812

## A 1.3285388 1.4552237 1.6838932 1.7658242 1.5804548 1.8069369

## v1 6.7084610 4.0459888 3.7720199 2.2243421 3.1182496 4.5875267

## v2 1.4177665 1.2421040 0.8438141 1.6249084 1.2687774 1.0955937

## t0 0.1056549 0.1586988 0.1706621 0.1210396 0.1335432 0.1640788

exp(subj_random_effects)

## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6] [,7]

## b1 1.0698792 1.18052156 0.8616525 1.0077446 1.25233908 1.0505038 1.13231721

## b2 1.5810594 1.01349667 1.0861553 1.5847698 1.35280872 1.2649702 1.30095455

## b3 1.7989528 1.46079588 3.1265433 1.7744359 1.38487043 1.8961407 1.99624056

## A 1.0477341 1.60317273 1.3586326 1.4905036 1.45768087 1.4372163 1.22752645

## v1 2.2520081 2.05856866 3.5213098 4.8296340 2.97284855 3.1347669 3.72293224

## v2 1.2324928 1.03178471 1.4013664 1.2345473 1.05132353 1.3223169 1.76704460

## t0 0.1736622 0.06164594 0.2817316 0.1773803 0.07388239 0.1544707 0.04397247

## [,8] [,9] [,10] [,11] [,12] [,13] [,14]

## b1 1.1835877 1.0231218 1.2171509 1.1485222 0.8366241 1.2285680 1.00945766

## b2 1.1692359 1.3818269 1.1829541 1.6147392 1.2244929 1.3279842 0.93130680

## b3 2.1254323 1.2458592 1.7940886 1.8074860 1.5426012 1.4924557 1.35255010

## A 1.7206290 1.1498150 1.5190524 1.5605442 1.2326995 1.8325463 1.15400527

## v1 3.4529753 2.2658188 4.9225426 4.4279333 2.0658373 5.3601733 2.71698668

## v2 1.6440032 1.3831821 1.4884682 1.4434504 1.1329634 1.5333058 1.55998953

## t0 0.1131715 0.1044828 0.2667479 0.1550111 0.0622914 0.1029939 0.05606001

## [,15] [,16] [,17] [,18] [,19] [,20]

## b1 1.22458829 1.1010562 1.175366 1.0384539 1.1303807 1.0827347

## b2 1.12606272 1.3007035 1.187601 0.9812187 1.1685068 1.3862862

## b3 1.13916786 1.8423449 1.278752 1.4076217 1.7183810 1.3376333

## A 1.38654314 1.3749288 1.662572 1.6381828 1.5902512 1.7317641

## v1 7.46232804 4.0204679 3.706521 1.9515447 3.2799533 4.4788415

## v2 1.41152663 1.4364761 1.077409 1.6080192 1.4342091 1.3536970

## t0 0.08848583 0.1441908 0.152783 0.1000067 0.1031465 0.1560934These seem to recover quite accurately. Next though, we need to check the covariance matrix;

sig<-sampled$samples$theta_sig[,,sampled$samples$stage=="sample"]

cov<-apply(sig,3,cov2cor)

cov2<-array(cov, c(length(pars),length(pars),1000)) ##1000 is the length of posterior sampling

colnames(cov2)<-pars

rownames(cov2)<-pars

apply(cov2,1:2, mean)

## b1 b2 b3 A v1 v2

## b1 1.00000000 0.27435761 0.02309705 0.03536069 0.16886207 0.18033331

## b2 0.27435761 1.00000000 0.13002183 -0.02399570 0.10831885 0.06176004

## b3 0.02309705 0.13002183 1.00000000 0.08640149 0.07622340 0.02414490

## A 0.03536069 -0.02399570 0.08640149 1.00000000 0.12468679 0.11164222

## v1 0.16886207 0.10831885 0.07622340 0.12468679 1.00000000 0.11637253

## v2 0.18033331 0.06176004 0.02414490 0.11164222 0.11637253 1.00000000

## t0 -0.25814657 -0.11025466 0.17354185 0.03909197 0.08641464 -0.20071341

## t0

## b1 -0.25814657

## b2 -0.11025466

## b3 0.17354185

## A 0.03909197

## v1 0.08641464

## v2 -0.20071341

## t0 1.00000000

cov2cor(sigmaC)

## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6] [,7]

## [1,] 1.0 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2

## [2,] 0.2 1.0 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2

## [3,] 0.2 0.2 1.0 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2

## [4,] 0.2 0.2 0.2 1.0 0.2 0.2 0.2

## [5,] 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 1.0 0.2 0.2

## [6,] 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 1.0 0.2

## [7,] 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 1.0Simulate Posterior

Following these checks, I simulate posterior predictive data from the posterior model estimates. For simulating from the posterior, I follow a similar method to that shown here. First taking some random posterior samples, and then using our likelihood function to simulate data (similar to the earlier synthetic data step). In this example, I use 20 posterior samples (this is a good start - you may want to use more). This means my posterior predictive data will be 20 times the length of my simulated data.

generate.posterior <- function(sampled, n){ #this function uses sampled$ll_func as the likelihood function to sample from

n.posterior=n # Number of samples from posterior distribution.

pp.data=list()

S = sampled$n_subjects

data=sampled$data

data$subject<- as.factor(data$subject)

sampled_stage = length(sampled$samples$stage[sampled$samples$stage=="sample"])

for (s in 1:S) {

cat(s," ")

iterations=round(seq(from=(sampled$samples$idx-sampled_stage) , to=sampled$samples$idx, length.out=n.posterior)) #grab a random iteration of posterior samples

for (i in 1:length(iterations)) { #for each iteration, generate data

x <- sampled$samples$alpha[,s,iterations[i]]

names(x) <- sampled$par_names

tmp=sampled$ll_func(x=x,data=data[as.integer(as.numeric(data$subject))==s,],sample=TRUE) #this line relies on your LL being setup to generate data

if (i==1) {

pp.data[[s]]=cbind(i,tmp)

} else {

pp.data[[s]]=rbind(pp.data[[s]],cbind(i,tmp))

}

}

}

return(pp.data)

}

pp.data<-generate.posterior(sampled,20)

tmp=do.call(rbind,pp.data)

glimpse(tmp)

## Rows: 120,000

## Columns: 5

## $ i <int> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, …

## $ subject <fct> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, …

## $ rt <dbl> 0.8109699, 1.3727252, 1.0959211, 0.4747878, 0.9924096, 2.803…

## $ resp <dbl> 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, …

## $ condition <int> 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, …Now we have data from the posterior, we can plot this data against our synthetic data.

#functions to find the 10th, 30th, 50th, 70th and 90th quantiles

q10=function(x) quantile(x,prob=.10,na.rm = TRUE)

q30=function(x) quantile(x,prob=.30,na.rm = TRUE)

q50=function(x) quantile(x,prob=.50,na.rm = TRUE)

q70=function(x) quantile(x,prob=.70,na.rm = TRUE)

q90=function(x) quantile(x,prob=.90,na.rm = TRUE)

#posterior rt data across quantiles

posterior <- tmp %>% group_by(i,condition) %>%

summarise("0.1"=q10(rt),

"0.3"=q30(rt),

"0.5"=q50(rt),

"0.7"=q70(rt),

"0.9"=q90(rt))%>%

ungroup()

#reshape

posterior<-posterior %>%

pivot_longer(

cols = starts_with("0"),

names_to = "quantile",

names_prefix = "",

values_to = "rt",

values_drop_na = TRUE

)

#synthetic rt data across quantiles

synthetic <- data %>% group_by(condition) %>%

summarise("0.1"=q10(rt),

"0.3"=q30(rt),

"0.5"=q50(rt),

"0.7"=q70(rt),

"0.9"=q90(rt))%>%

ungroup()

#resahpe

synthetic<-synthetic %>%

pivot_longer(

cols = starts_with("0"),

names_to = "quantile",

names_prefix = "",

values_to = "rt",

values_drop_na = TRUE

)

synthetic$condition<-as.factor(synthetic$condition)

posterior$condition<-as.factor(posterior$condition)

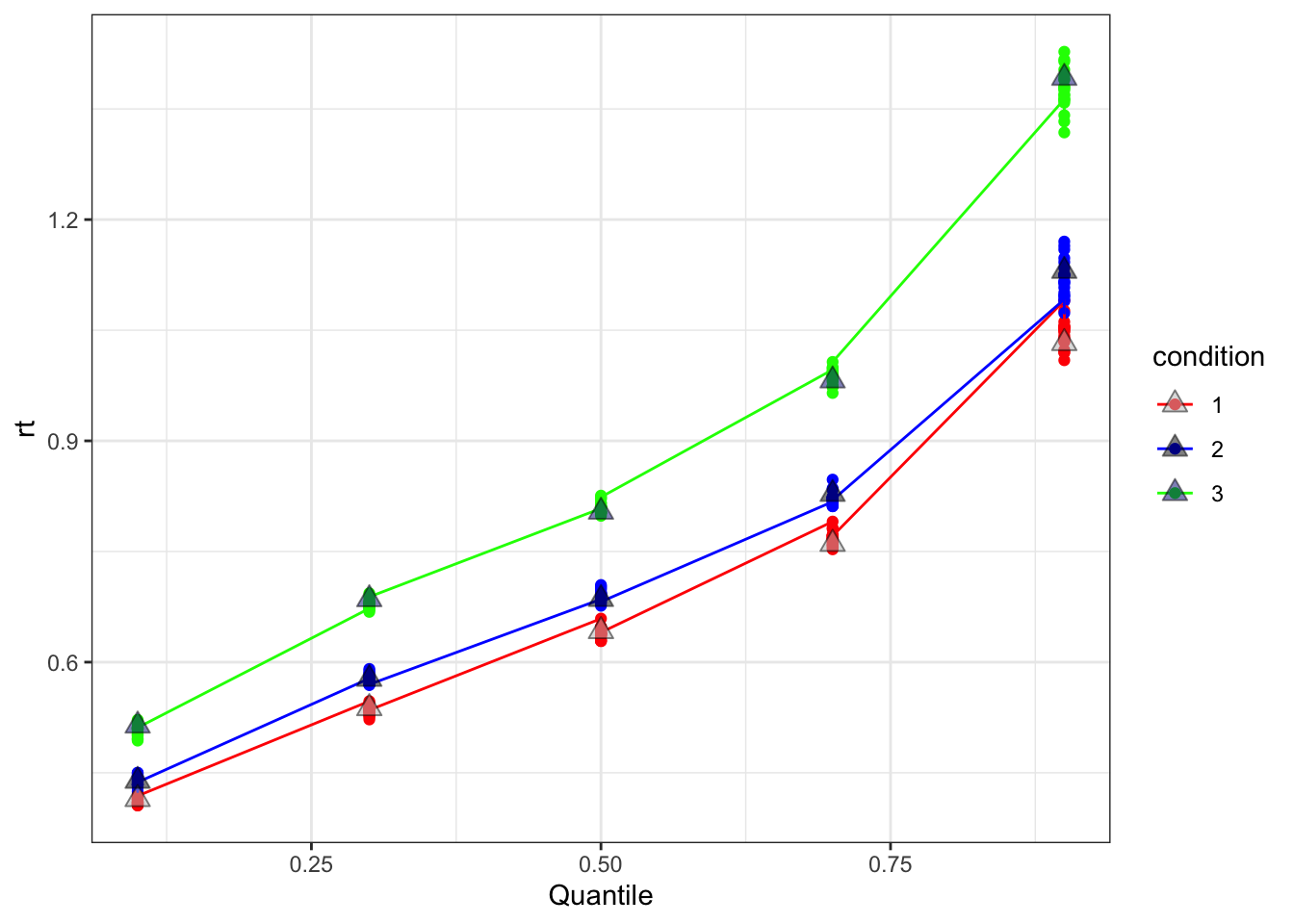

#plot - this is only for RT. Also may want to plot accuracy

ggplot(posterior, aes(x=as.numeric(quantile), y= rt))+

geom_point(aes(colour = condition))+

xlab("Quantile")+

scale_color_manual(values = c("red", "blue", "green"))+

geom_line(aes(colour = condition))+

scale_color_manual(values = c("red", "blue", "green"))+

geom_point(data=synthetic, aes(x=as.numeric(quantile), y= rt, fill = condition), shape = 24, size=3, alpha = .5)+

theme_bw()+

scale_fill_manual(values = c("grey", "black", "navy"))

This graph shows RT on the y-axis across quantiles (x-axis) for both the simulated (grey triangles) and posterior recovery data (shown as coloured dots for each posterior iteration and lines for the means). Here we see the posterior recovered samples appear to match the synthetic data quite well, as we expected.

Conclusion

Simulation and recovery practises are important for any modelling exercise. It is important to be familiar with the methods to perform simulation and recovery so you can be confident in your log likelihood function being reliable and valid (in regards to theory). This blog post aimed to explain methods of simulation and recovery for the PMwG package, and provide a framework to allow such practices.